There’s only story in popular music in 1991 that most people care about: it’s the year that punk broke. “Smells Like Teen Spirit” came out in September and everything immediately changed forever.

That’s the story, at least.

In reality, the shift from mainstream rock to alternative was as gradual as the shift from the Tyrannosaurus rex to a McChicken. The dialectical struggle between mainstream and underground has been a feature of rock music since the late 1960s; once the Beatles and Elvis helped make rock music pop music, there were immediately acts in the wings trying to be more real, more experimental, more human. From the cosmic Neptunian bluegrass of the Grateful Dead to the gleefully constructed rebellion of the Sex Pistols, the Jungian shadow of rock music has danced in the dark for decades.

What makes 1991 a convenient data point for the dramatic break from the past is that it marks the moment that the mainstream turned itself inside out. We talk about 1977 as the year of punk rock, but the biggest album of the year was Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours; more than that, the biggest singles of the year were Debby Boone’s “You Light Up My Life,” the Bee Gees “How Deep is Your Love,” Andy Gibb’s “I Just Want to Be Your Everything,” the Emotions “Best of My Love,” and Barbra Streisand’s “Love Theme from A Star is Born”––not exactly edgy material. You and I may associate 1988 with Daydream Nation, but people at the time were listening to “Faith” and “Never Gonna Give You Up.” We write the history of pop music in a way that makes people think everyone was buying Ramones and Dinosaur Jr. records, but that’s just because the underground won, and we all know who gets to write the histories. 1991 is the mainstream’s Waterloo––"I was defeated / you won the war." In that way, it’s fair to say that 1991 is, indeed, the breaking point, but it wasn’t lightning in a bottle; it was the end of a long, harsh campaign.

Honorable Mentions:

Metallica, Metallica (The Black Album); Soundgarden, Badmotorfinger; Throwing Muses, The Real Ramona; Codeine, Frigid Stars LP; King Missile, The Way to Salvation; Primus, Sailing the Seas of Cheese; Beat Happening, Dreamy; Hole, Pretty on the Inside; Spacemen 3, Recurring; BUCK-TICK, 狂った太陽 (Kurutta Taiyo); The Orb, The Orb’s Adventures Beyond the Ultraworld; Pearl Jam, Ten; American Music Club, Everclear; Pixies, Trompe le Monde; Queen, Innuendo; Halo of Flies, Music for Insect Minds; Sepultura, Arise; Fugazi, Steady Diet of Nothing; Muhal Richard Abrams Orchestra, Blu Blu Blu; Red Hot Chili Peppers, Blood Sugar Sex Magik; Billy Bragg, Don’t Try This at Home; Swans, White Light from the Mouth of Infinity; Richard Thompson, Rumor and Sigh; Coil, Love’s Secret Domain; Giant Sand, Ramp; Jonathan Richman, Having a Party with Jonathan Richman; Del tha Funkee Homosapien, I Wish My Brother George Was Here; Dead Can Dance, A Passage in Time; The Wedding Present, Seamonsters.

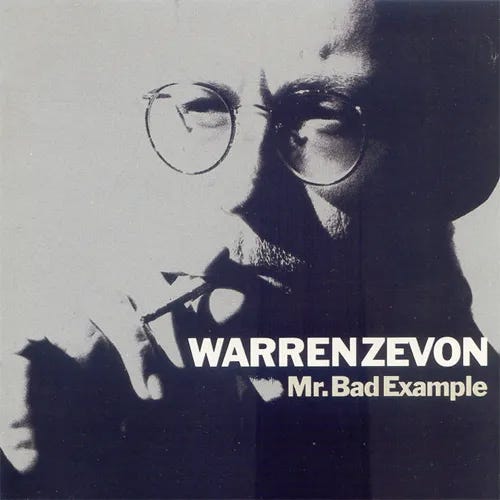

20. Warren Zevon – Mr. Bad Example. Warren Zevon had exactly one Top 40 hit single (1978’s “Werewolves of London” off his third record Excitable Boy), and although it’s more associated with Tom Cruise playing pool in the movie that won Paul Newman his Oscar (Martin Scorsese’s 1986 sequel to The Hustler, The Color of Money) than it is with the artist behind it, that flash of success conceals a singer-songwriter of extraordinary depth and crackling wit, a wisecracking and literary man outside of time.

The son of a Jewish gangster from Chicago and a Mormon mom, Zevon’s musical career got started early, scoring a Top 100 single in 1966 (“Follow Me”) as half of a high school duo called Lyme and Cybelle. By the time of the release of his seventh solo full-length, Mr. Bad Example, he was a 44 year old man, a Los Angeles troubadour and troublemaker with a small whiff of the left behind. That reputation was completely unearned––the record starts off with a bang in “Finishing Touches” and never lets up, a lean and whip-smart compilation of guitar-bass-and-drum singer-songwriter rock. “Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead” lent its name to a forgettable post-Pulp Fiction Andy García crime flick, but don’t hold that against it.

Mr. Bad Example is not Zevon’s best album––it lacks the pugnacity of Excitable Boy or the tragic weight of 2003’s The Wind––but it’s an incredibly worthy installment in a criminally overlooked career.

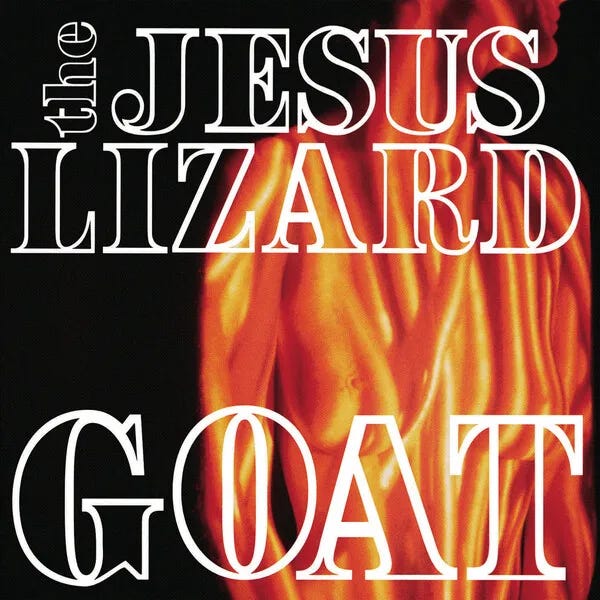

19. The Jesus Lizard – Goat. I know that I am not alone in spending most of the time that I’ve known of the Jesus Lizard with a misunderstanding of the cover of this record. The cover image of Goat is not a flame; it’s a topless woman with an image of nails projected against her skin. This is a surprisingly effective metaphor for the album itself––it presents itself as one thing, but when you look closer, it’s something at once more familiar and more unsettling.

There’s a stereotype that noise rock bands don’t write songs, but that’s never really been true; what noise rock bands do is vivisect them, crack the sternum and take out the still-beating organs and rearrange them. Bands before the Jesus Lizard explored this space (Big Black, White Light/White Heat-era Velvet Underground), and there have been many worthy successors to them as well (Lightning Bolt, Melt-Banana), but David Yow and co.’s Austin-based outfit perfected the template. A track like “Mouth Breather” exemplifies this––opening with a blistering guitar riff from Duane Denison that quickly gets subsumed into David Wm. Sims and Mac McNeilly’s thunderous rhythm section while the onomatopoeic Yow wails over it. The whole record is like this: jagged, uncompromising, difficult, and somehow astoundingly catchy. On Goat, the Jesus Lizard descend into Hell to harrow it, and drag us back into the light when they ascend.

18. The KLF – The White Room. A funny thing happened on the UK pop charts in the spring of 1988: a mash-up of the iconic theremin-driven Dr. Who theme song and the ubiquitous sports thumper “Rock and Roll” shot to number one. Panned by critics but embraced by cackling audiences, the novelty hit’s path to the top was elucidated in a book published shortly thereafter called The Manual (How to Have a Number One the Easy Way) by pomo pranksters Jimmy Cauty and Bill Drummond, also known as the Timelords.

Here’s another story: in 1975 the American Discordian episkopos, agnostic mystic, and libertarian futurist Robert Anton Wilson co-wrote a series of books collected into The Illuminatus! Trilogy, a drug-sex-and-black-magick-fueled anarchist kaleidoscope of counterculture and conspiracy theory. One of the (many) secret societies vying for world control in the book is the Justified Ancients of Mummu (or “the JAMs”), and in the year before “Doctorin’ the TARDIS” went to number one, a mysterious outfit called the Justified Ancients of Mu Mu (or “the JAMMS”) released a track called “All You Need is Love,” based around samples of the titular Beatles song, the MC5’s “Kick Out the Jams,” and Samantha Fox’s “Touch Me (I Want Your Body)” to critical acclaim and popular indifference. The signature Scottish bark-rapping over the top was from a man named Bill Drummond (“King Boy D”), who put the song together with his friend and partner-in-crime Jimmy Cauty.

Here’s one more story real quick: in 1990 a group called the KLF invented ambient house with their LP Chill Out, a particularly laid-back and spacey form of then-popular house music, itself a descendant of disco. After the success of that record, they blew it up to mammoth proportions and released The White Room, originally a soundtrack for a film that was scrapped early on. The White Room would be the group’s last testament, but it was a titanic one, with four singles released that lit up the underground dance scene in Europe and sketched out a future for electronic music as a whole. The KLF made rave music listenable to normal audiences; as famed critic Robert Christgau put it, the record had “everything I like about house and [they] are canny enough to can the boring parts.”

The final single off this record and the last commercial release from the KLF? “Justified and Ancient.”

17. Michael Jackson – Dangerous. By 1991, the King of Pop was well on his way from the world-conquering Michael Jackson of 1982 to the, let’s say, more complicated figure of today. Dangerous comes after the near-fatal Pepsi commercial incident and the increasing rumors of his plastic surgery and strange behavior, and before the first allegations of misconduct. It’s an easy record to overlook, given that by now Michael was well on his way out of music stardom and into pure Michaelness.

We’re not going to talk about all that though.

Dangerous gives us more than enough to talk about on its own. The record is a major step forward artistically, arguably the last vital release of the biggest American pop star since Elvis Presley. Jackson is pushing forward here, embracing rap and new jack swing from the jittery opening “Jam” (with an appearance from Heavy D on the bridge and a music video in which Jackson teaches Michael Jordan how to moonwalk) on, and crafting sonic textures at such an incredibly high level of quality and innovation that you can hear, as critic Joseph Vogel points out, the roots of everything from Nine Inch Nails to Lady Gaga in them. Jackson is in top form all over the record, growling desperately on “Why You Wanna Trip on Me” and hitting pop heights on smash hit “Black or White.” So much of 1990s pop music is in here, and you can hear the future Michael that could’ve been all over the record. He would have one more real commercial triumph of original music (1995’s HIStory, which included “You Are Not Alone,” the first single to debut at number one on the Billboard Hot 100), but by then he was already starting to be defined by the allegations against him. He would be a major touring act and pop culture icon until his 2009 death, and in retrospect Dangerous’ title serves as an astute warning of what awaits when an imperial phase starts to crumble.

16. Mekons – The Curse of the Mekons. If you’re unfamiliar with the British punk lifers the Mekons, then I’m sorry to break to you that you have fallen prey to the titular curse. Formed in Leeds way back in 1976, the Mekons have choogled along since, still bringing down the house with chaotic live shows and even making pretty solid records almost fifty years into their career. So what’s their problem? Well, nobody really pays attention to them. Hence, the curse.

Long critical darlings (Robert Christgau named two of their records to the top of his famed Dean’s List, 1985’s Fear and Whiskey and 2002’s OOOH!), the Mekons remain under the radar of most listeners, and it’s really too bad––there’s no other group that really sounds quite like this. Initially a straight-ahead British punk band, they began incorporating country influences into their sound in the mid-80s, and then a bit of a dub reggae in 1988’s So Good it Hurts, and staked out an early indie rock gem in The Mekons Rock & Roll the year after. By 1991’s Curse, they’d pulled out the cowboy hats again, making the best alt-country record of the early 90s. Opener “The Curse” slinks out like a hoodoo Stones B-side, catchy and shambolic, and the album never really shifts out of this gear (to its enormous credit), even when it’s covering John Scott Sherrill’s “Wild and Blue” or slowing down a bit for groover “Nocturne.” The Curse of the Mekons is really just one installment in a career of epic length, but it’s one worth putting aside the time for.

15. Died Pretty – Doughboy Hollow. Australian jangle rockers Died Pretty are basically unknown stateside, and it’s too bad; a kind of Aussie R.E.M., the band released eight albums between 1986 and 2000 before they broke up in 2002, and with frontman Ron S. Peno’s death in 2023, the possibility for more releases has officially been foreclosed.

Doughboy Hollow is generally considered the band’s best, nominated for multiple ARIA Awards in 1992 and called the 96th best Australian album of all time by Rolling Stone Australia, a magazine that I only recently learned existed. The record starts strong with “Doused” (a song weirdly reminiscent in the verses of Tom Petty’s “Learning to Fly,” which came out this same year) and into hit single “D.C.,” and the quality never falters. Earning comparisons to Paisley Underground bands like the Dream Syndicate, Died Pretty sketch out a swirling, vivacious world anchored to an antipodean reality specific to their Sydney life, filtered through late 60s Dylan and the Velvet Underground. The sounds on Doughboy Hollow might be familiar, but the soul is new.

14. R.E.M. – Out of Time. My wife was scandalized to see how low Out of Time fell on this list, and I understand why; some of Athens, Georgia legends R.E.M.’s best songs are on here––I’m partial in particular to “Losing My Religion,” “Near Wild Heaven,” and “Half a World Away.” The heights are undeniable; what keeps Out of Time relatively low for me is, well, the lows. “Radio Song” is a fine single, marred by an inexplicable KRS-One verse. “Shiny Happy People” is a song I like more than many (in particular I’m fond of the B-52s’ Kate Pierson’s harmonies and the expertly placed handclaps) but I understand people’s aversion. Much of the rest of the deep cuts are, unfortunately, just forgettable.

But boy oh boy––those heights. I have nothing really to say about “Losing My Religion” that hasn’t already been said, but everything that’s been said is right; it’s a perfect single. I want to set aside a moment to reflect on “Near Wild Heaven,” a bouncy Byrds homage from bassist Mike Mills. An acidic breakup song wrapped in sugary harmonies and chiming guitars, it’s an ironic, almost nasty slice of power pop cherry pie, an excellent evolution for the long-running band.

R.E.M. were one of those bands that started incredibly strong (1983’s Murmur) and never really stopped being great. Even their 20th century output, largely met with yawns outside of two popular singles from 2001’s Up (“All the Way to Reno (You’re Gonna Be a Star)” and my favorite of the two, the Douglas Sirk-referencing “Imitation of Life”) is all basically solid. And my wife is right; Out of Time is great. It’s just not R.E.M. great.

We’ll talk more about Michael Stipe and co. in the next installment of this column, though.

13. De La Soul – De La Soul is Dead. In 1989, Long Island rap trio and Native Tongues alumni Posdnuos, Trugoy the Dove, and Maseo teamed up with producer Prince Paul and created one of the best and most influential records of all time in 3 Feet High and Rising. The popular perception of De La at the time was that they were hippies, an image that wasn’t helped by the Day-Glo cover art of that first record or the recurring references to the “D.A.I.S.Y. Age” (that’s “Da Inner Sound, Y’all”). Reteaming with Prince Paul for their second outing, they were determined to move past this stereotype, starting with the cover: a painting of a broken vase of daisies.

The music, at first blush, is just as bouncy and effervescent as 3 Feet High and Rising, but there’s a harder edge here, both in the production and in the lyrics. Prince Paul is credited with introducing the lamentable practice of inserting comedy skits into rap albums, but here they’re used sparingly and well, providing a sardonic tinge to the energy. From early standout “Oodles of O’s” (built around a sample of Tom Waits’ “Diamonds on My Windshield”) to the sad irony of “My Brother is a Basehead,” every track is catchy and sharp-elbowed, a divergence from daisification that would continue into 1993’s Buhloone Mindstate and beyond; the trio would release their last record (And the Anonymous Nobody…) in 2016, seven years before founding member Trugoy’s too-early death.

12. Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers – Into the Great Wide Open. Gainesville natives Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers released their first self-titled LP in 1976, earning two smash hit singles in “Breakdown” and “American Girl.” Fifteen years later, they’d release “Learning to Fly,” the first track off Into the Great Wide Open and one of Petty’s most enduring hits, culturally and commercially. They’d continue to release records until 2014’s Hypnotic Eye, the last before Petty’s tragic opioid overdose a few weeks before his 67th birthday in 2017.

The erstwhile King of the Hill voice actor was a particular kind of American icon, a backwoods Springsteen who crawled out of the swamps to the bright lights of LA––not the seedy Hollywood underground, though. Petty was a Valley boy, and he sang like it. That was the late troubadour’s great strength: Axl Rose may have come out of the country to brave the city, but Tom Petty just wanted a house with a yard in Reseda. Into the Great Wide Open is a sprawling, Neil Young-like exploration of this sort of domesticity, a particularly bucolic entry in a vital songwriter’s discography.

11. Smashing Pumpkins – Gish. The First Lady of American Cinema was born in Springfield, Ohio in 1893. Ranked by the American Film Institute as the 17th-greatest female movie star of classic Hollywood, Lillian Gish remained active for three-quarters of a century––beginning in silent shorts in 1912 and ending in 1987, six years before her death in 1993. At some point in those 75 years, she also rode a train through a town in the middle of nowhere; it was the biggest thing that happened in that town’s history, and became a major part of the town’s history. Many years later, a woman who saw her waxed poetic about this brush with stardom to her grandson Billy, who decided to name his band’s debut record after just this incident.

Chicago heavy rockers Smashing Pumpkins arrive fully formed on Gish. It’s all there: Billy Corgan’s tremulous whine, his and James Iha’s guitar theatrics, D’arcy Wretzky’s jackhammer bass, and thunderous drums from Jimmy Chamberlin. The band that would score major hits with Siamese Dream (1993) and Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness (1995) is here, bringing to life their patented blend of shredding psychedelic alt-rock. “Siva” takes the grunge loud-quiet-loud formula to new extremes, while “Rhinoceros” trips and flies over a slinky guitar lead. From back-to-front the entire record bangs like a lead zeppelin, and though their next two records would reach even higher, it’s still one of the strongest debuts of the alternative era.

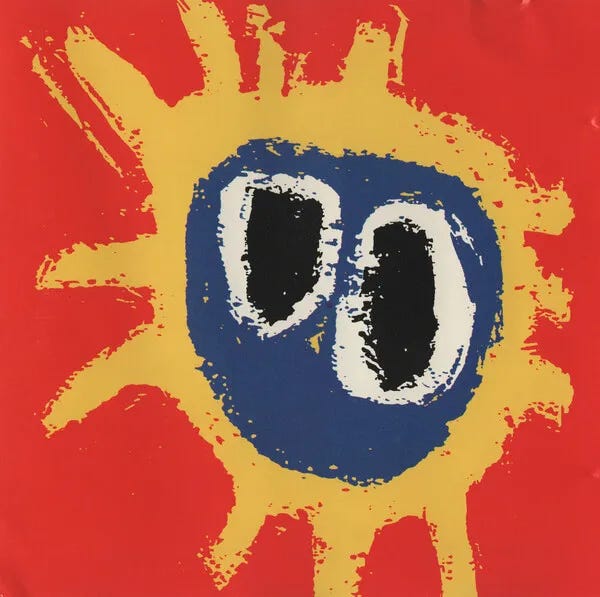

10. Primal Scream – Screamadelica. In my last column, I talked a bit about the history of the Madchester scene through the lens of Happy Mondays, and now it’s time to focus on another one of the heavy-hitters of that dance-infused underground movement: Primal Scream (who were Scottish, not Mancunian, but certainly a kind of Mancunian of the soul). The best song on this record, and the best song by the band, and one of the best songs of the 1990s, is the first: “Movin’ on Up,” a gospel-infused rave-up that sounds like Exile-era Mick Jagger time traveled to a Haçienda show in 1989. It’s a perfect song, the kind of track that you hear and feel like you've known your whole life. If it was released just as a single, with no accompanying record, it would still probably make this list.

Thankfully there is an accompanying record, and although it never hits the high of “Movin’ on Up” (how could it?) it’s enjoyably diverse and experimental, moving from its opener immediately into the straight-up sitar and wah-bass driven dance beats of “Slip Inside This House.” The production, helmed by late acid house DJ Andrew Weatherall, could certainly be accused of a certain datedness, but it somehow never comes across that way––that Stonesiness keeps it rooted in classic British rock, and the dance flourishes (the synth flute on “Don’t Fight It, Feel It” anyone?) don’t make it feel 90s, they just make it feel like it came from Jupiter. Groovier and dancier than many of its contemporaries, Screamadelica manages to create an entire new genre under the skin of another.

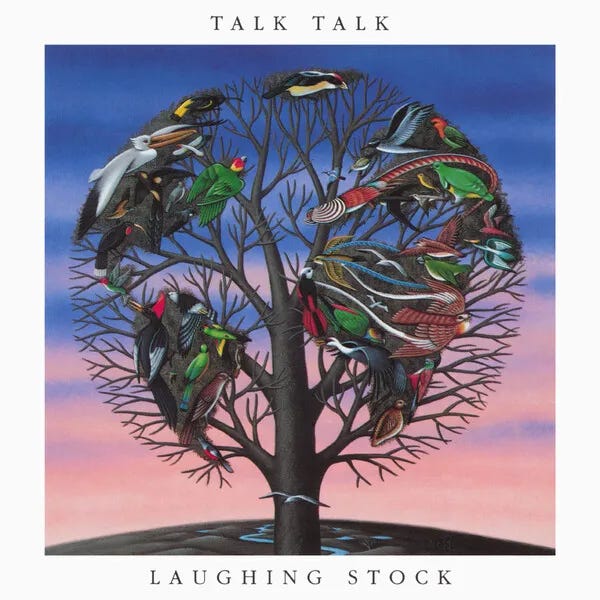

9. Talk Talk – Laughing Stock. Speaking of creating new genres––let’s talk about post-rock. Talk Talk began life as a London synth-pop trio in 1981, notching their most enduring hit in 1984’s “It’s My Life,” later covered to great success by Orange County icons No Doubt in 2003. Then, like James Murphy said, they threw out their arpeggiators and bought guitars for 1986’s The Colour of Spring––still firmly in the New Wave framework, they started introducing jazz and art pop influences under the aegis of increasingly monomaniacal bandleader Mark Hollis. It was a hit in Europe, the band’s biggest in fact, landing two hit singles (“Life’s What You Make It” and “Living in Another World”) staying on the UK charts for 21 weeks. Two years later, they blew it all up Spirit of Eden, diving even deeper into the artsy jazz world and incorporating elements of classical, dub, ambient, and all kinds of other music that relies on texture more than melody. Pop music historians agree: this was the beginning of post-rock, a moody and intellectual subgenre that uses traditional rock instrumentation for non-rock purposes. The record was not a success, and its follow-up, Laughing Stock, would be the group’s final album (Mark Hollis died from cancer in 2019, ensuring that it would maintain that status).

The record itself is tremendous––as sprawling and intoxicating as its reputation suggests. It’s a solid 7-8 minutes into the 43:29 album before you hear a human voice; opener “Myrrhman” is two and a half minutes of pure texture and vibe. It’s beautiful; the album sulks and slinks and invites you but never lets you near. As a capper to a career, it’s a masterpiece; as a starting pistol for a genre, it’s necessary.

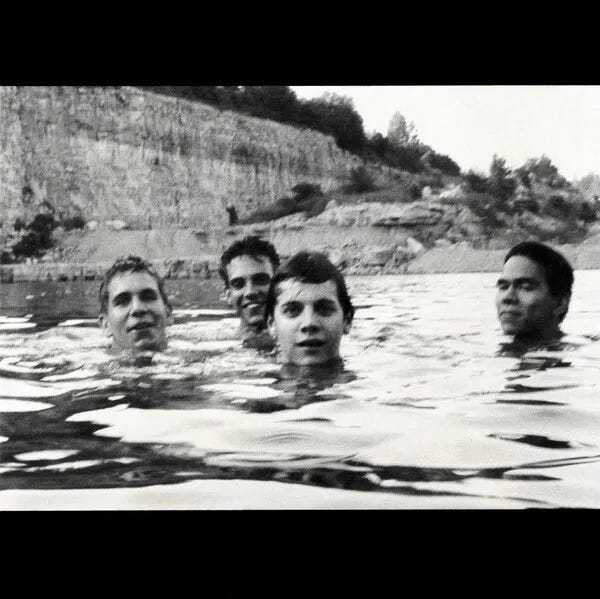

8. Slint – Spiderland. Oh look, another opportunity to talk about another underground subgenre of alternative music: math rock. Similar in structure at times to post-rock, math rock is typified by strange rhythmic structures and complex time signatures––King Crimson’s post-Crimson King work (1974’s Red and 1981’s Discipline in particular) are seen as early touchstones alongside other particularly boundary-pushing progressive acts of the 1970s, but Spiderland is really where it comes together.

Slint’s second and final album comes off like if Steve Albini produced a Yes record; it’s intricate and complex but it doesn’t try to transcend. Instead, it’s as murky and difficult to pin down as its cover art, moody and punishing; the harmonics on “Breadcrumb Trail” turn into something more sharp and sinister on “Nosferatu Man,” with a snarling electric-shock guitar riff that wouldn’t be out of place in an AOL log-in screen. The vocals are either shouted or whispered, with Brian McMahan’s tetchy lyrics detailing narratives of unease and despair while his guitar wraps around David Pajo’s virtuosic lead lines. The entire thing is a monument, the sort of work that makes you feel emptier for having experienced it but better the next day. This is the 90s Marquee Moon.

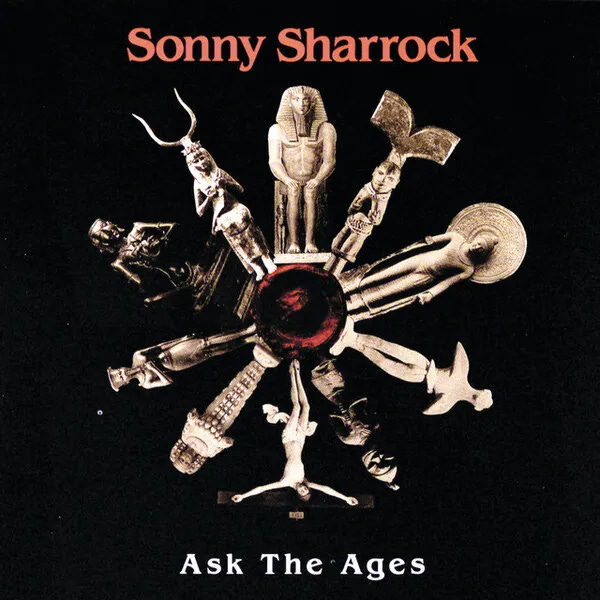

7. Sonny Sharrock – Ask the Ages. J. Mascis of Dinosaur Jr always wanted to play the drums; instead, he played the guitar like it was the drums. Free jazz legend Sonny Sharrock had a similar origin story––inspired to pick up the tenor saxophone after hearing Coltrane on Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, he quickly realized that being a 19 year old asthmatic was not conducive to fulfilling brass section dreams. Instead he picked up the guitar, later identifying as “a horn player with a really fucked up axe.” And he’s right––he plays guitar like how Coltrane played the sax.

The next year Sharrock played electric guitar, uncredited, on one of my personal favorite albums of all time: A Tribute to Jack Johnson, Miles Davis’ underrated 1971 jazz-funk opus. He released three records under his own name, often collaborating with his wife Linda, between 1969 and 1975, disavowing the last of these (Paradise) and going into semi-retirement until the early 1980s. Bassist Bill Laswell coaxed Sharrock back to the scene in 1981 for his band Material’s album Memory Serves and the elusive guitarist remained active until his 1994 death. He had two projects in the 90s that helped define his career and ensure his legacy.

The first is Ask the Ages. The final record of his released in his lifetime, it’s 45 minutes of post-bop perfection. Produced by Laswell, it features saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, bassist Charnett Moffett, and drummer Elvin Jones in a tight quartet, keeping an angular groove under the volcano of Sharrock’s emotive, golden guitar playing. It feels like an artifact from the 60s heyday of Mingus and Hancock, something completely out of time. Sharrock was close to signing his first ever major label contract when he died at the age of 53. It’s a shame that he never put together a follow-up to this titanic effort, but it’s a hell of a note to go out on.

The second major project of the 1990s, by the way, is the Space Ghost Coast to Coast theme song, done in collaboration with drummer Lance Carter.

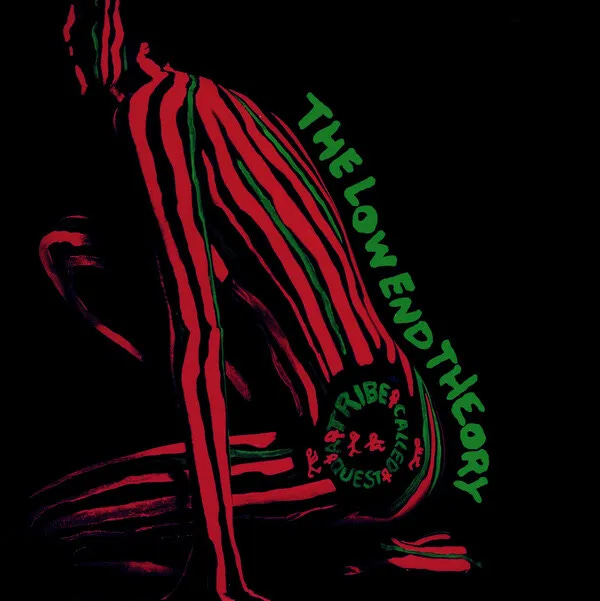

6. A Tribe Called Quest – The Low End Theory. The same Native Tongues scene that launched De La Soul also birthed A Tribe Called Quest, intellectual and jazzy where De La was sugary and chilled-out. The Low End Theory, Tribe’s second album, is anchored with dusty drum loops and jazz double bass, allowing Q-Tip and Phife Dawg to slip and slide over the beats, trading barbs and bits the whole way through and even including newcomers like Busta Rhymes, whose career would be launched by his appearance on “Scenario.”

This leaner stripped-down sound is my favorite iteration of Tribe; the more traditionally sample-based production of their debut People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm left me cold enough to leave it off my 1990 list (although I like the expansiveness of their last album We Got It from Here… Thank You 4 Your Service in 2016, released a few months after Phife Dawg’s death), but this is the peak for me. Each track soars, and the lyricism on the opening one-two punch of “Excursions” and “Buggin’ Out” are both top-notch, spinning around in ear-worm rhythms that have run in the background of my head since high school. Truly one of the vital rap records of the early 90s.

5. Massive Attack – Blue Lines. A recurring theme in 1991 is the new––this is the year when the ground shifts.

That makes it all the more moving that the best song Blue Lines is the one that sounds the oldest: closer “Hymn of the Big Wheel.” Roots reggae legend Horace Andy harmonizes with Neneh Cherry (the adopted daughter of jazz legend Don Cherry) about the looming environmental destruction of the world over an African and dub-inflected melody and the only backing track on the record devoid of samples––just snapping drum machines and a slinky synth bass anchoring the pulsating rhythm. It’s an impressively warm and human capper to an album that effectively invents the genre of trip-hop.

Wikipedia defines trip hop as “a psychedelic fusion of hip hop and electronica with slow tempos and an atmospheric sound, often incorporating elements of jazz, soul, funk, reggae, dub, R&B, and other genres, typically of electronic music, as well as sampling from movie soundtracks and other eclectic sources,” and although impressively long-winded I see no issue with this definition. Born in rainy Bristol in the late 1980s, Blue Lines solidifies this sound, which will be expanded upon in future years by the solo work of Massive Attack member Tricky and the ethereal trio Portishead. In a way, Massive Attack bookends the genre’s golden age with this and 1998’s Mezzanine; this is probably the superior record. Each track is moody and complex, deeply satisfying, especially the aforementioned closer and opener “Safe from Harm,” creating a swooning and chilly must-have of modern British music.

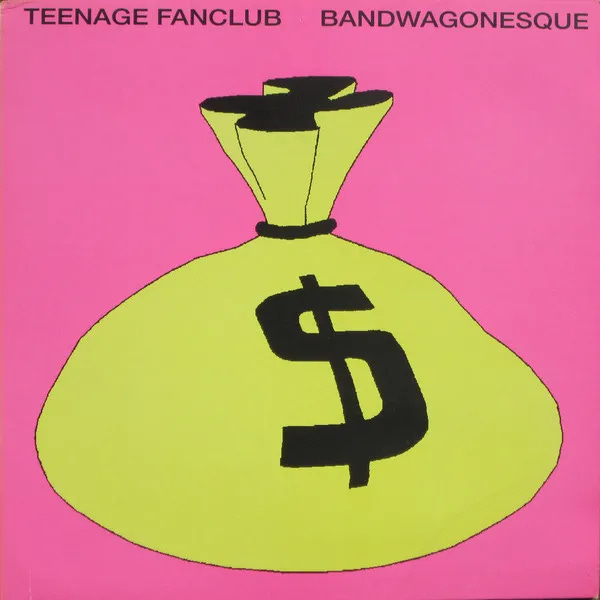

4. Teenage Fanclub – Bandwagonesque. Things became very complicated very quickly for Scottish noise-poppers Teenage Fanclub after the release of their first album A Catholic Education in 1990. That record was released in North America by then-fledgling New York indie label Matador and made a solid critical splash in the UK––enough to get the attention of bigger labels. Matador head Gerard Cosloy alleges that tossed-off odds-and-ends collection The King (also 1991) was a way to get out of their contract; the band denies this, but the effect is the same: Teenage Fanclub joined up with Creation Records, and at almost exactly the wrong moment, too. Creation released Bandwagonesque on November 4, 1991 in the UK, the same day they also released My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless, an album two years and a quarter-million pounds in the making that almost completely bankrupted the label (they’d try to stay alive with a Hail Mary in the ensuing years, signing a small-time Beatles and Kinks tribute act and releasing their first record in 1994; thankfully for Creation, that act was Oasis, and that record was Definitely Maybe).

Although Creation wasn’t necessarily able to give Bandwagonesque the push it needed in the UK, Geffen was able to in the US, spawning three Billboard Modern Rock Tracks top 20 hits (“The Concept,” “What You Do To Me,” and “Star Sign”) and making Teenage Fanclub a major player in the power pop sub-scene of the 90s. Their success in the UK would come––across the pond, their biggest hit would be 1997’s Songs from Northern Britain––but it’s Bandwagonesque that made a splash here.

And for good reason! The Big Star acolytes of Teenage Fanclub do justice to their heroes, crafting pop perfection on pop perfection, crooning and sighing in multipart harmony through waves of shimmering noise. The entire record is a journey and a joy, a slice of power pop perfection that still sounds fresh today.

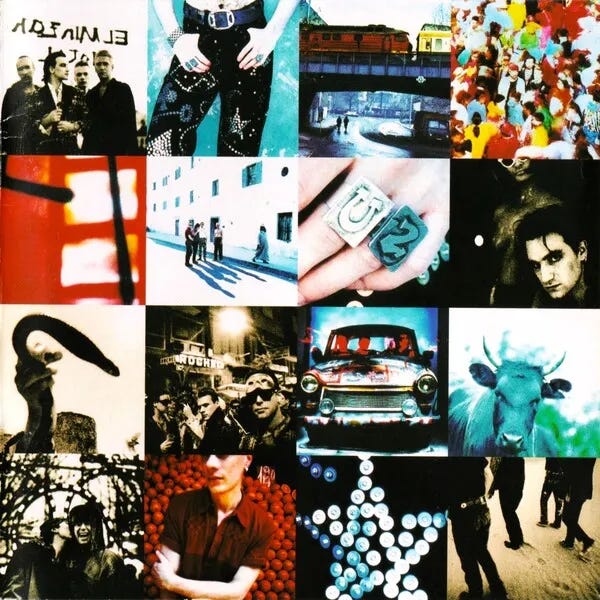

3. U2 – Achtung Baby. I’ve gotta be honest: I never really liked U2. I think my first knowing exposure to the band was seeing the video for “Sweetest Thing” on MTV as a kid, a Joshua Tree B-side that was released as a single to promote a best-of in 1998. I didn’t really register them as a band at that time though; I was in third grade, and more interested in Dookie and “Flagpole Sitta.” My first real experience with them was All That You Can’t Leave Behind in 2000, and especially “Beautiful Day,” which my fifth grade ears found corny as hell.

I didn’t know, though; I was unschooled. I can only plead ignorance. When Bowling for Soup released “1985” in 2004, I was confused about why they were referencing U2 as a band from the 80s. Weren’t they the “Vertigo” guys? My dad was a metalhead and my mom liked Red Hot Chili Peppers and rap; I wasn’t raised on the lovable lads from Dublin.

So I went back. I did my diligence. A U2-fan friend played me the Johnny Cash-featuring “The Wanderer” off Zooropa, which I really dug. I listened to “Sunday Bloody Sunday” and “New Year’s Day.” I listened to The Joshua Tree. I saw Bono take “Helter Skelter” back from Charles Manson. I was starting to understand.

But I didn’t, really, until Achtung Baby. Oh, I’d heard the hits; I knew “One,” I knew “Mysterious Ways.” None of this could prepare me for this record. It’s a phenomenal achievement. From the Madchester-influenced distortion of opener “Zoo Station” to the piano-driven closer “Love is Blindness,” Achtung Baby (named in response to the fall of the Berlin Wall) is a roadmap of the 90s from one of the 80s’ biggest bands. It’s a testament to the ability to stay current that it still doesn’t sound dated; the band is able to find the soul of the song and keep its heart beating even now. The prism of Achtung Baby has made me re-examine U2’s entire discography, and fruitfully so. Every alternative rock act in the 90s has DNA in either this or Nevermind. It doesn’t sound like anything else, then or now. It’s the sound of a veteran band at the peak of their powers, and it will sound exactly the same one hundred years from now.

I still think “1985” was wrong to include U2 in the chorus––not because they’re not an 80s band, but because they’re a forever band. That process began in the shimmering mirage of The Joshua Tree, and it ended in the gleam of Bono’s fly sunglasses on Achtung Baby.

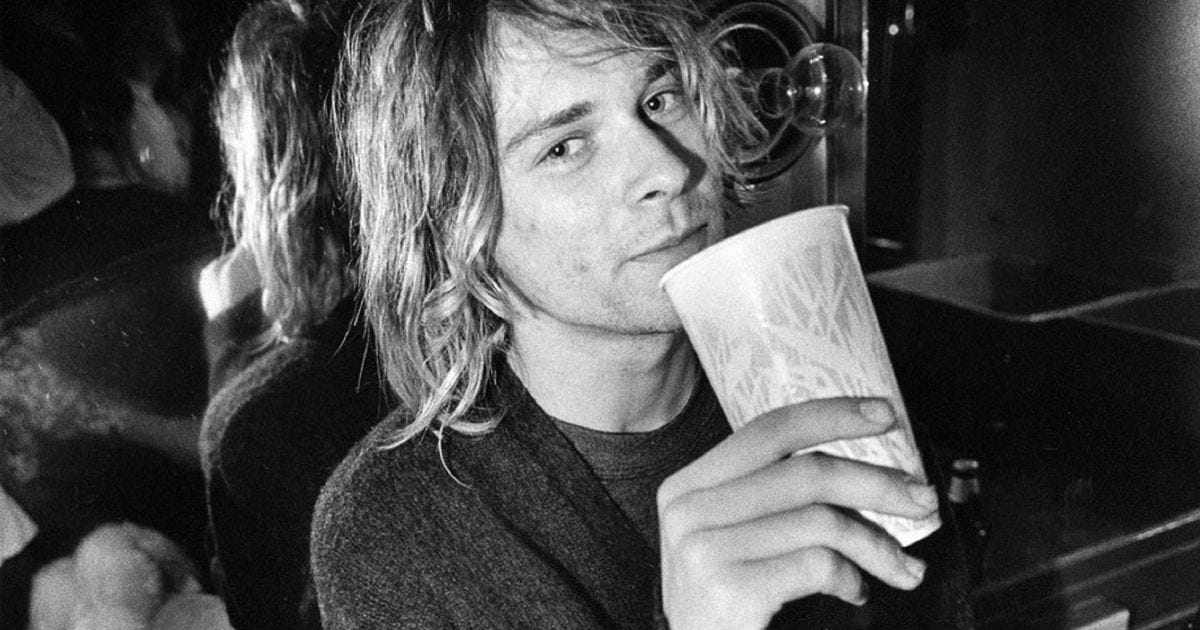

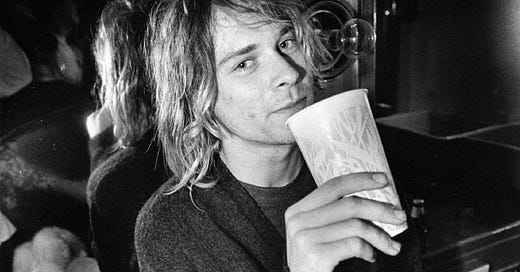

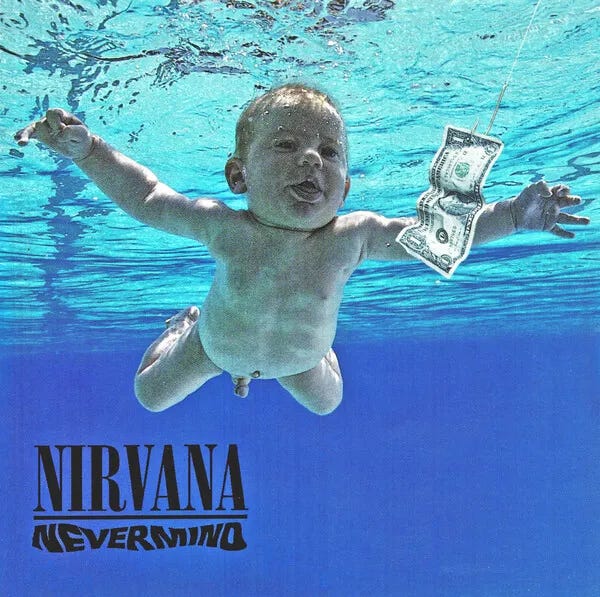

2. Nirvana – Nevermind. About 2500 years ago a confused young man sat under a tree in Northern India until he figured everything out. “We hurt,” he realized, “because we are attached.” Letting go is the only way of escaping the cycle of suffering, and in so doing, reach enlightenment. This moment of realization is known now as when Siddhartha Gautama reached nirvana––translated as “blowing out,” “extinguishing,” “liberation.”

Thousands of years later and on the other side of the planet, another confused young man reached Nirvana––or at least, he reached Krist Novoselic and Dave Grohl, and with them recorded a record called Nevermind. Like the prince who became the Buddha, he made a pretty big splash (to say the least). Like the band’s namesake, it was not destined to last. It was, indeed, extinguished.

Here’s something pop culture smart alecks like me sometimes fail to realize: Sometimes everybody is right. Some years, a record comes out that changes everything, and everyone agrees it’s great, and it is. Nevermind is one of those records; comparable in scope to something like Thriller or Revolver, it’s one of those before-and-after moments. There’s Music BN (Before Nevermind), and there’s Music AN (After Nevermind). This is the record that ushered in the revolution; this is Lenin on wax.

Etc., etc.

It’s easy to over-mythologize important works of art. Nothing I said before is wrong, but it’s not complete. The universe did not actualize itself through Nirvana; or, if it did, it did it through human beings, with feelings and ideas. Kurt Cobain was not born to be an agent of change; he was just born, like all of us. He proved to be a pop music genius, an unwashed McCartney, and like many men thrust into destiny he was crushed by it. The fates are not friends of man––but we’ll talk about that more in 1993.

So let’s talk about the music. It’s great. Each track is a thrill. You know all the singles by heart, but the deep cuts (“Breed,” “Drain You,” “On a Plain”) are all astounding too. It’s got an extraordinary staying power, the kind of deep and broad work that continues to offer new things to new audiences; who would’ve guessed moody (semi-)closer “Something in the Way” would become Gen Z anthem after The Batman?

Comedian Anthony Jeselnik once said that “art is getting away with it”; by that definition, Nevermind is one of the defining works of art of the 1990s, and maybe of late 20th century America in general. Three Sasquatches from the Pacific Northwest declared war on mainstream rock and did it by writing the catchiest, noisiest punk songs ever laid down––and they got away with it. The fates would catch up to them, but as of 1991, they had reached nirvana.

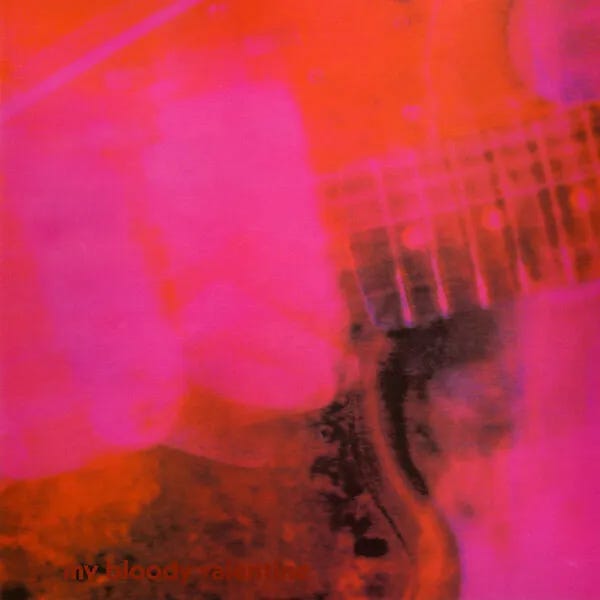

1. My Bloody Valentine – Loveless. The decision on what to name number one of 1991 was a surprisingly fraught one; some days it was Nevermind, some days it was Achtung Baby, some days it was Loveless, some days it was even Bandwagonesque. Any one of these could reasonably be called the best of the year; they’re all canonical albums. This is not totally uncommon; wait until we hit 1968 on the backswing and have to parse between Electric Ladyland, Bookends, Village Green Preservation Society, Odessey and Oracle, The White Album, Sweetheart of the Rodeo, White Light/White Heat, etc., etc. To love art is to be a Croesus, a Mansa Musa, a Scrooge McDuck, diving constantly into the smothering depths of riches.

At some point, though, you have to choose.

About ten weeks before my nineteenth birthday my buddy Marc and I stood, exhausted, in a dry stretch of polo ground in the California desert as My Bloody Valentine helped close out the 10th annual Coachella Valley Music & Arts Festival. We had gone for one night two years previous, getting to see the Jesus and Mary Chain, Björk, Jarvis Cocker, and more, but this time we were camping out. The Cure headlined that last night in 2009, but to be honest I don’t even remember them. My Bloody Valentine came right before them on the main stage, and I have a distinct memory of having never experienced anything louder in my life, before or since. It was a transporting wave of noise, a psychedelic frequency; I was a straight edge teen and I’ve never felt higher. It was the kind of experience that makes you wonder if MBV is a CIA operation, if they’re flooding your brain with aural chemicals that will some day trigger and make you feel compelled to assassinate a third world dictator.

What’s really incredible about Loveless is that that feeling is there, on record, if perhaps in miniature. Irish bandleader and insane person Kevin Shields spent a quarter-million pounds and two years delicately tweaking hardware and wiring together new kinds of pedals in order to create a soundscape so intricate that it feels like magic (and when I say that, think Aleister Crowley, not David Blaine). Filmmaker Paul Schrader in his book Transcendental Style in Film talks about how cinema’s unique property as an art form is its ability to sculpt in time; it decides for you how you experience a moment, how long or how quickly it goes by. Loveless succeeds in sculpting with sound, summoning spiral glass parapets out of the sea salt sand and inviting you to marvel at them just long enough to understand, before Bilinda Butcher’s somnambulant vocals pull you off to somewhere else. It’s a monumental artistic achievement and sincerely timeless.

There was shoegaze before Loveless and shoegaze since; even today, young people continue to experiment with turning up amps too loud and running them through weird filters until what comes out the other end sounds like something other than music. What there hasn’t been and cannot be is another Loveless. Like Trout Mask Replica or The Lord of the Rings, it’s an irreplicable moment. You can’t go home again, but if you’re lucky, you can get a glimpse God in the desert, roiling through you in ancient sound.

I know this is completely unasked for, but I simply cannot resist making a list. This time none of my faves made your list (my top for 1968 isn’t even among your hypotheticals). I promise not to do this every time (but 1992 is a strong year and I won’t be able to fnord resist at least that).

1. Frank Tovey & the Pyros, Grand Union

2. Violent Femmes, Why Do Birds Sing?

3. Oak Ridge Boys, Unstoppable

4. Baltimore Concert, Watkins Ale

5. Jennifer Warnes, Famous Blue Raincoat

That's another way of saying I really enjoy these writeups.

R.E.M. was on repeat in the ENCINITAS TRADER JOES BACK IN THE DAY! Our captain- SAM- loved OUT OF TIME and in turn so did we🫶🏽✔️great music era!!:)